Just after midnight on May 30, 1907, firemen lounging in their San Jose firehouse were jolted by a ghastly sight: Frank Boronda, a fellow firefighter, standing in the doorway, screaming uncontrollably.

Boronda lived next door, and his convenient commute turned into a crucial source of medical attention that night. He was covered in blood, and the firemen soon discovered why.

His penis had been cut off.

The firemen rushed Boronda to a nearby Red Cross hospital, perhaps just missing the woman who fled from the house next door. Dressed like a man, she slipped into the dark.

Long before Lorena Bobbitt became a national punchline, the Bay Area had Bertha Boronda.

Bertha was Frank’s second wife, and perhaps he thought this marriage would be more peaceful than his first. His first wife, Serena, married him around Christmas in 1890. Less than three years later, she made the local news for attempting to kill herself by drinking chloroform. When asked why she did it, Serena said Frank was physically abusive. Recently, he’d abandoned his wife and step-daughter altogether.

The pair were granted a divorce in 1895 and six years later — on Christmas Day — Frank married Bertha Zettle.

Not much is known about Bertha. Census records show she was born in Minnesota to German immigrant parents. The 1900 census lists her residence as a boarding house in Snohomish, Wash., working at a laundry. In the next year, she must have met Frank. She was 24 when they married in 1901.

Frank’s given name was Mario Narcisso Boronda and much more is known about him. His great-great-grandfather was one of the first teachers in San Francisco and helped build the Presidio in the late 1700s. The Boronda family grew and spread, settling all over the nascent Bay Area.

Frank, it seems, wasn’t one of the family’s more illustrious members. After his divorce, he made headlines for another scandal. In February 1907, he and another fire captain were arrested on suspicion of committing election fraud. They were questioned and released, but Frank worried he hadn’t escaped charges.

On May 29, he took Bertha to the theater. According to her later court testimony, it was the first time they’d spoken in two weeks. The second Mrs. Boronda found about as much marital bliss as the first: Bertha said they’d been married just over a year when she began to suspect he was stepping out on her. For six months, Bertha lived alone in San Francisco, working as a saleswoman at the Emporium. Frank wrote letters, begging her to reconcile, but, when she did, she said things weren’t much better. Frank would disappear for weeks at a time, and Bertha’s only recourse was to walk next door to the firehouse and beg him to talk. He ignored her.

That night at the theater, Frank told Bertha he suspected he was about to be re-arrested for vote buying. Perhaps he thought it would be best to reconcile with his wife before a potential court case. Or perhaps he was just lonely. Bertha told the court that after they went home, she tearfully asked if he still loved her. He swore he did — and then he asked for sex.

At that point, Bertha claimed she blacked out. Testimony from police and firemen fills in the gaps. After Frank fell asleep that night, Bertha found his straight razor. Then, she tiptoed back to bed and sliced off his penis.

In the melee, Bertha switched into a disguise, donning her brother’s suit for her getaway. Bertha admitted she’d worn it frequently — she was surveilling her husband to determine where he went after work. She guessed she’d slept one, maybe two, hours a night for the past few weeks.

She wasn’t on the lam for long; police found her a few hours later, still dressed as a man.

According to Bertha, she remembered nothing of the maiming. She only recalled waking up in the San Jose city jail. A police officer asked if she wanted something to eat. She requested coffee.

When police asked her what had happened, Bertha said she was convinced Frank was about to leave her and move to Mexico.

And, she said, she wasn’t sorry.

Her 1908 trial was a sensation, covered by just about every newspaper in the Bay Area. Bertha stood accused of “mayhem,” defined by state law as any “person who unlawfully and maliciously deprives a human being of a member of his body or renders it useless, or cuts or disables the tongue, or puts out an eye, or slits the tongue, nose, ear or lip.”

Several witnesses testified Bertha made repeated threats of violence against her husband if she caught him cheating again. One said Bertha declared she would “blow his head off.”

She sat calmly for the duration of the trial, accompanied at times by her family.

“While she shows the effects of her incarceration and the loss of sleep, she does not seem to be nervous,” the San Jose Times Star wrote.

At one point, Bertha testified she found letters from multiple women in Frank’s possession. One, interestingly, was from Lillian Doane, the daughter of his first wife. More about their relationship isn’t known, but Bertha’s testimony seems to imply their correspondence was romantic in nature.

Regardless of the scene of marital discord Bertha presented, one thing was undeniable: She’d done the deed.

The jury deliberated only a few hours before returning a guilty verdict.

Bertha was sentenced to five years in San Quentin, which at that time still housed female inmates. (California wouldn’t have a dedicated women’s prison until the 1930s.)

Her incarceration was a quiet one, at least according to the papers. Sometimes her family came to visit and, at some point, she and Frank divorced.

Both married again, Frank in Monterey County and Bertha in Los Angeles. Frank died in 1940 at the age of 76. Bertha died 10 years later; she was 72. Neither, it seems, ever had children.

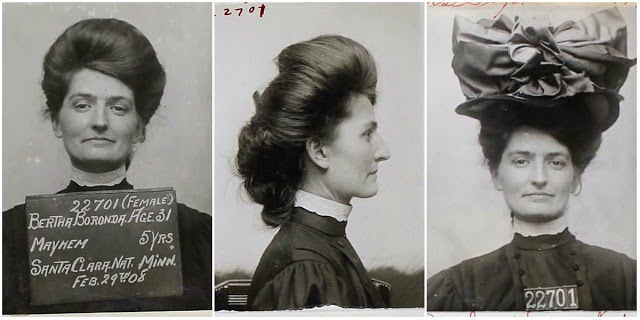

All that now remains of Bertha Boronda are her mugshots from the day she was booked at San Quentin.

Leave a Reply